Once he returned to Slighhouses, Hutton practiced what he had learnt, introducing new husbandry to Berwickshire and to what he refers to it as a cursed country, an outpost of civilization, uncultivated with a lack of tools and skilled tradesmen. At the time Slighhouses was described as an open field, with rig and furrow which Hutton removed and replaced with ditches.

With the benefit of the new husbandry Slighhouses was described at the time by the author and advocate Robert Forsythe;

“The doctor began in earnest to improve a very wild and uncultivated piece of land; all of it was an open field, stones were to be split, fences were to be made at great expense being on the border of sheep country; drains also innumerable. The tillage also was all performed with the Suffolk plough. Dressing the land, drilling and hoeing turnips, rolling and all the operations of husbandry were done to a degree of neatness and gardenlike culture which in farming had not been seen before. Persons from every description came from every quarter to gratify their intellectual curiousty as well as to get information”.

He developed the Berwickshire husbandry of clean turnip fallows, neat ploughing and the introduction of cultivated grasses. This involved a crop rotation which was wheat, turnips after 6 months of fallow and barley undersown with grass and clover. He kept cattle and probably sheep. Hutton loved his cattle which were black polled, similar to the Aberdeen Angus breed.

‘Give me joy’

he wrote in a letter

‘this day is born unto my family a male child, mother is in a fair way of recovery. Though if the ladies were but capable of loving us men with half the affection that I have towards the cow and calvies that happen to be under my nurture and admonition what a happy world we should have’.

There are no contemporary records for Nether Monynut and there are no old 18th century buildings, all appearing to have been converted sometime during the late 19th century. It is probable however that Nether Monynut being a hill farm maintained a sheep flock and lambs were fattened on turnips at Slighhouses.

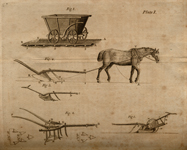

Hutton endeavoured to improve Scottish agriculture. The Scots plough used at the time was heavy, clumsy, inefficient and wooden. In Norfolk he purchased what he described as a ‘high suffolk’ plough, hired a ploughman and brought them both on a post chaise with him to Berwickshire. The neighbours were intrigued with this assortment of companions and belongings and no less with his attempt to plough with a horse in front and no driver, so he obviously caused a stir. Hutton probably worked with James Small at Blackadder Mount near Chirnside in Berwickshire, who designed the famous swing plough.

He experimented with plants and animal husbandry including animal nutrition and the dynamics of light, heat, soil chemistry and it was apparent that he had a growing interest in geology, and meteorology. He considered the relationship between climate, heat, and plant growth using insultated thermometers to investigate the relationship between temperature and latitude, the degree in Fahrenheit drop with each degree of latitude and the fall in temperature with evaporation. He attempted to predict harvest dates by relating the average temperature with the ripening corn, estimating that one degree drop in average temperature brought the harvested back by 1.5 weeks. He also experimented with soil fertility, using salt,

seaweed, dung, coal ash and marl. He excavated his own marl pit at Slighhouses which still exists, though it will be smaller now than it was when he worked it. Quantities commonly spread were

“sometimes to the extent of 400 two-horse loads per acre” !.

Hutton proposed a system of agriculture which aimed to maintain soil fertility with mixed farming and rotations and the judicious use of fertilisers. He was conscious of political and economic need and that agriculture and wealth provide the stability of a nation.

James Hutton did not appear to publicise his innovations and was not recognised at the time for his contribution to agriculture, other than by the French Societe Royale d’Agriculture de Paris which elected him an ‘associe etranger’.

While at Slighhouses he toured the northeast of Scotland in 1764 with George Clerk-Maxwell. His geology and agricultural studies were inseparable.